Rachel Parsons was a woman ahead of her time. With her paternal grandparents being polymaths and her father an engineering genius, and with formidable engineering skills and dedication herself, she should have been a huge success. She founded engineering societies and companies, entertained the cream of London’s gentry and royalty and crossed swords with many august bodies, but war, estrangement and tragedy stalked her life and she was to die in mysterious circumstances at another’s hand.

Rachel Mary Parsons was born on the 25th of January 1885, at 10 Connaught Place, the London home of her paternal grandparents, the third Earl and Countess of Rosse of Birr Castle, Birr, Kings County (now County Offaly), Ireland. Her father, the Honourable Charles Algernon Parsons, was the youngest of their eleven children and married Katharine Bethell, daughter of William Bethell of Rise Park, Hull, Yorkshire, in 1883

Her grandfather, William Parsons, third Earl of Rosse, was an Oxford mathematician and a most eminent astronomer. One of his most memorable achievements was ‘The Leviathan of Parsonstown,’ the aptly named then-largest telescope ever built. The massive instrument, constructed in the grounds of Birr Castle in the early 1840s, retained its world record for three quarters of a century. His wife, Mary Wilmer Field, a wealthy heiress, was an accomplished blacksmith and an acknowledged pioneer in the field of photography. As Lady Rosse she partly designed and constructed much of the framework which supported ‘The Leviathan,’ which she also financed, and she received an award from the Photographic Society of Ireland in respect of her ‘fine paper negatives’.

Rachel’s father and his younger brother were privately tutored by Professor Sir Robert Ball, one time Professor of Applied Mathematics at Royal College, Dublin and of Astronomy and Geometry at Cambridge, as well as being the Royal Astronomer of Ireland. Perhaps, therefore, given such an illustrious tutor, it is not surprising that Charles Parsons was rightly recognised as one of the greatest engineers of his time, his most renowned invention being the ‘Steam Turbine,’ which powered the Chilean navy (before he was able to convince the British Government of his ingenuity), the ‘Dreadnought’ and such famed ocean liners as the ‘Mauritania’ and the ‘Lusitania’. He was knighted in 1911 for his contribution to technology and awarded the Order of Merit in 1927, three years before his death.

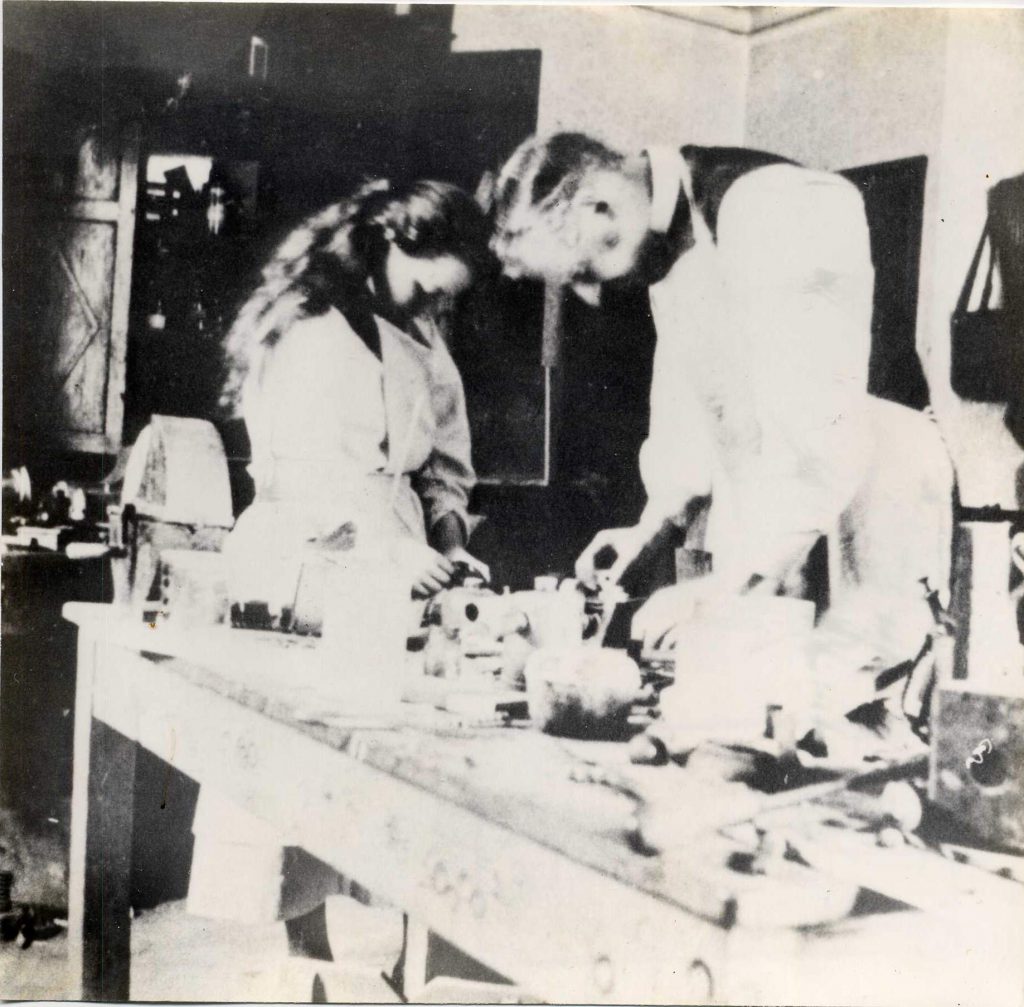

Charles and Katharine Parsons had two children, Rachel Mary (1885-1956) and Algernon George (1887-1918) the latter affectionately known as ‘Tommy’. Both children had an inherent enthusiasm for their father’s ingenuity and invention, working with him on various projects at their home-workshops within their Tyneside homes of Elvaston Hall, Ryton and, later, Holeyn Hall, Wylam. There they experimented in the making of turbine powered experimental machines and mechanized toys propelled by methylated spirit, such as helicopters and the ‘spyder’. The latter thrilled the children as it sped around the drawing room floor decanting sparks and setting fire to the carpet, which Rachel and Tommy eagerly extinguished by running after the creation, stamping upon the smouldering areas with their feet. Rachel would accompany her father onboard ‘Turbinia’, the prototype, turbine-propelled craft, whilst the ship was undergoing various trials after it’s launch, in 1894. She remained quite unabashed, despite getting very wet and risking sea-sickness, and sailed with him to America, aboard the ‘Mauretania’, in 1909.

With the excitements of her childhood and following schooling at Newcastle High, Wycombe Abbey (Clarence House, May 1899 – April 1900) and Roedean (September 1900 – July 1903), Rachel’s paramount interest was engineering. In April of 1910 (a particularly unusual time to join) she was enrolled at Newnham College where she studied Mechanical Sciences, under Professor Hopkinson, but only for five terms, until Michaelmas Term 1912. During that time she took the preliminary examination for Part I of the Tripos and a qualifying exam. in Mechanical Sciences in 1911. However, and for whatever reason, the prevalent myth, that she took the tripos, with honours, followed her for the rest of her life. Equally strangely, not she nor her parents made any effort to stifle this claim, which friends close to the family, at least, must have known to have been untrue.

It was not too unusual at that time for students to take rather less than the entire Tripos; indeed it was fairly common practice for male students, before the First World War, to take few, if any, of the Tripos examinations. Customarily, women more readily did so, but her decision may well have reflected her position, insomuch that she had rare, advantageous opportunities available, which caused her to consider it unnecessary to proceed with the full Tripos.

Tommy Parsons followed his father into Parsons Marine Steam Turbine Company at Heaton, Newcastle- upon- Tyne but his career was short lived, due the onset of the 1914-18 war, loosing his life in action on the 26th of April 1918. Major A.G. Parsons rests in Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery, in Belgium. Rachel, in the meanwhile, had very successfully deputised for her brother as an Alternative Director at Parsons’ Heaton Works, fully expecting to continue in this position after the end of the war. However, the devastating loss of his son would not suffer Charles Parsons to grant his daughter a full company directorship or to continue in her brother’s role, which dealt her a devastating blow, and altered her character for the rest of her life. This caused a rift in what had been an idyllic relationship between father and daughter, which was never reconciled and consequently, she resigned her position.

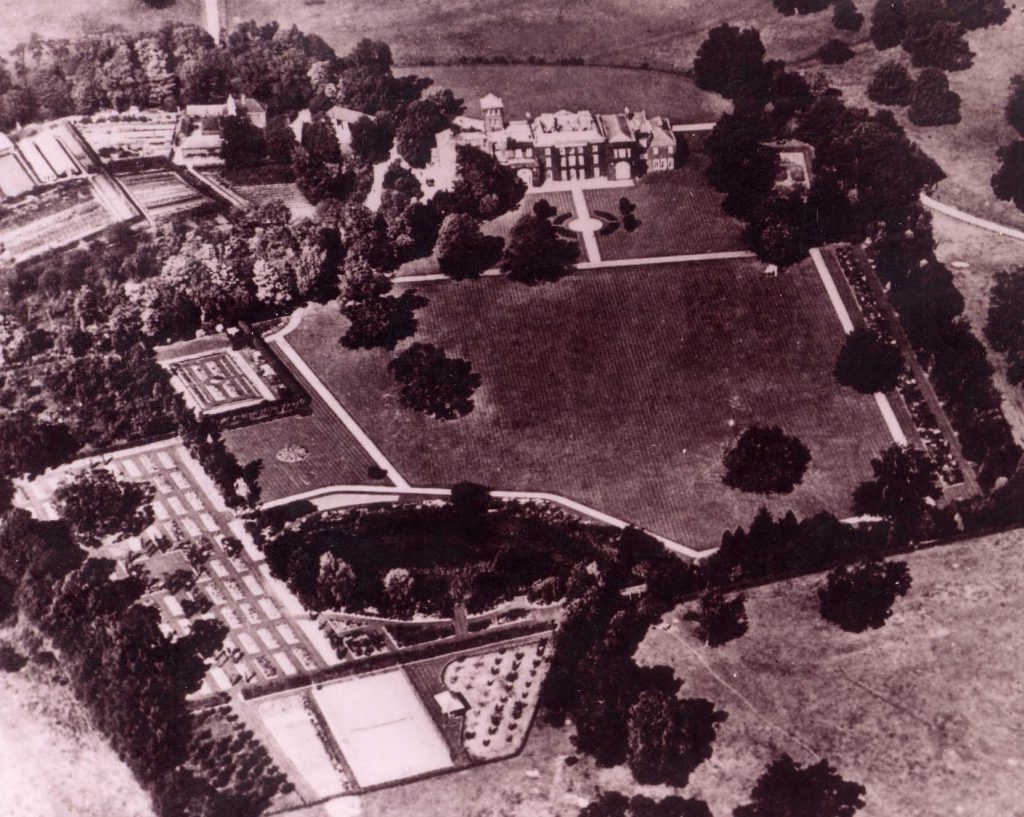

Sir Charles chose not to return to Holeyn Hall after the death of his son but neither did he dispose of their former, much treasured, home. This shrine to happier times was not sold until after Lady Parsons’ death, in 1933. In order to continue his country pursuits, Charles bought Ray Demesne, a ten thousand acre estate at Kirkwhelpington, Northumberland, which Rachel retained until she disposed of it to the Ministry of Agriculture, in 1950.

In 1918, Rachel became a member of The Royal Institution of Great Britain, a membership that she retained until her death. This was an early demonstration of how keen she was to emulate her father, a very active member of that institution, who gave a number of Friday evening lectures on the steam turbine.

Severely determined to prove her capabilities to her father, Rachel, helped by her mother, and vehemently inspired by her experiences during her war effort in the Ministry of Munitions, founded the Women’s Engineering Society, of which she became first president in 1919. Rachel, Lady Parsons and the members of the WES championed the rights of women to work as engineers and for them to be allowed to continue with the employment they had taken on in place of their male counterparts, who had been required to join the war services. An exceedingly articulate and erudite account of the intentions of the WES, written by Rachel, was printed in ‘The Queen’ (15th March 1919 edition). Having had many eminent presidents, such as Amy Johnson (1935-1937) this society continues to the present day.

As stated in Lady Parsons’ obituary, “She was one of the founders of the WES and when in 1920, eight girls started an engineering company with a factory in London, she assisted the new enterprise.” In fact, the enterprise, Atalanta Ltd., was first established in Loughborough, specialising in the manufacture of “Oil Burners, hand scraped Surface Plates, Inventors’ Models and Accurate Machining and fitting to your drawings”. The aforementioned surface plates were “guaranteed accurate to + or – 0001”. The thirty-five year old Rachel Parsons was one of these ‘girls’, along with notable, young engineers Caroline Haslet and Annette Ashberry. Lady Parsons and Lady Eleanor Shelly-Rolls (heir to the car fortune) were the principal shareholders. These pioneers were dedicated to equalising the roll of women in the engineering industry, which was their foremost aim, although perfection of their finished product was imperative. The firm relocated to Fulham Road, SW6 by 1922 and to Brixton Road, SW9 in 1925. By 1927 the list of shareholders names, mainly women, was hugely impressive but in 1928 the company was voluntarily wound up.

In 1921, Rachel joined the membership of The Royal Institute of International Affairs and remained a member until her death.

1922 saw Rachel becoming a member of the London County Council, as a representative for Finsbury, and in that same year, she became one of the first three women members of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects, together with Blanche Thornycroft, (a member of another elite engineering family). By now Rachel was beginning to assume her own identity and this was especially demonstrated by her move from her parents’ home in Upper Brook Street to 5, Portman Square, where she was immediately able to unleash her desire for social recognition. The first of her social events to be reported in ‘The Times’ was a dinner and dance, which she gave on the fourteenth of July 1923. The carefully chosen guest list included two princesses of Greece, Lady Louis Mountbatten, the Danish Minister and his countess wife, a duchess, a marquis, and several dozen titled persons.

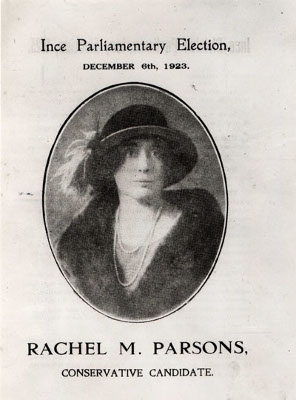

In December of 1923, Rachel stood as Conservative candidate for Ince, Lancashire, in the General Election of that year but was defeated in that Labour stronghold. Merely to stand was quite a feat, as Nancy, Lady Astor had become the first woman M.P. only four years earlier. By this time she had made a number of influential political friends, her election address stating her postal address as being 80, Cadogan Square, which was the home of the Duchess of Westminster.

1926 saw Rachel move to a considerably larger home at 5, Grosvenor Square, which boasted vast public rooms and a ballroom, suitable for accommodating up to five hundred guests. Indeed, so spacious was this fine house, the accommodation surpassed that available at many an hotel. Consequently, Rachel ‘let it out’ to her friends, who wished to give ‘coming out’ parties for their debutante daughters. The lavish entertainment of Royalty and an array of distinguished foreign diplomats of every sort continued until the outbreak of World War II, with a final small dinner at which the Duke and Duchess of Kent were guests. Things were never again to be quite the same.

In 1931, Sir Charles died, whilst on holiday in Bermuda. When the amount of his estate was published at £810,000, it was assumed that Rachel inherited everything, and this assumption dogging her to her last day, resultant of the ignorant insensitivity of the press. Preciseness dictates that Sir Charles left over £1,200,000 of which Rachel was left a quarter share of the residual estate, after the payment of death duty and a considerable number of bequests to family members, friends, work colleagues and institutions. Rachel, in fact, received little more than one tenth of her father’s estate although, of course, she had been substantially provided for during her father’s lifetime. The bequest to four of his nephews, amounting to half of his residual estate, had an incalculable effect on Rachel. This can be seen by her reaction towards most of her family members of Parsons descent, from whom she divorced herself for the rest of her life.

Lady Parsons died in 1933. Rachel didn’t attend her funeral, claiming indisposition. Under the terms of Lady Parsons’ will, Rachel received little and, as was her manner, now cut ties with most members of that family. The few exceptions included her father’s brother the Reverend Randal Parsons, rector of Sandhurst and the sixth Earl and Countess of Rosse.

Rachel continued to pursue her political ambitions, attempting to enlist help from friends who were suitably connected, such as Lady Astor, but with no avail. As late as 1940, she put her name forward for adoption as Conservative parliamentary candidate for Newcastle, North but was unsuccessful in her bid.

Unfulfilled and undeterred by threat of war, Rachel embarked for New York, aboard the luxurious liner, SS ‘Normandie’ on the 26th of August 1939. Less than three months after her political defeat in Newcastle, North, in April 1940, she returned to New York and from there sailed to Bermuda. One can detect but can fully understand the frustration of wartime, felt by this ambitious woman. Now aged fifty five years, she was painfully aware of her advancing years, presenting herself as some fifteen years younger than she was, to which passenger lists bear testimony. With the destruction of London in progress and the rest of the world becoming less accessible, Rachel decided that a move to a more rural location was required. In 1940, she bought ‘Little Court’, a beautiful Georgian-style house within twenty-five acres of land, at Sunningdale, Berkshire. This was sufficiently far from the devastation of her beloved London but still conveniently close for her to invite friends. Once established, the redoubtable Miss. Parsons ensured self-sufficiency, growing her own vegetables and rearing ducks (“The only reason I bought the place,” she told friends) and other such requirements to enable the presentation of a less frugal dining table than was usual in wartime.

One can only surmise as to how she engaged herself until she had a dramatic change of lifestyle in the early months of 1946, when she sold her Grosvenor Square home to buy 43, Belgrave Square. However, when the widowed, Princes Marina, Duchess of Kent placed 3, Belgrave Square on the market, Rachel bought it without delay in August of that same year. This was to remain her London home for until she sold it, only a few weeks before she met her death, having bought an apartment in Hyde Park Gardens. ‘Little Court’ was sold to Terrence Rattigan.

As keen racecourse attendee (although she seldom placed a bet) and despite her sixty-two years, she decided to take up racehorse owning, breeding and training, buying the 2,600-acre Branches Park estate, some miles from Newmarket. For the next nine years, this lover of animals was strenuous in her efforts to build up her stable of thoroughbreds, which numbered seventy-three horses at the time of her demise. Because of numerous disputes with The Jockey Club, generated mainly because a woman had entered a male-dominated recreation, she was banned from exercising her horses on The Heath. Undeterred, she purchased the Lansdowne House racing stable, in 1954, which had lain empty for some two years. This acquisition made her only the second owner/trainer/breeder with a private trainer, in Newmarket.

After experiencing several burglaries at Branches Park, this talented engineer invented a burglar prevention system, consisting of a mass of trip wires, connected to twelve-bore cartridges, which were affixed to the door posts of each room, around average head height. As there is no known report of a single victim, word of mouth must have prevented the need for cure! However, in the spring of 1956, Rachel moved into a few rooms in Lansdowne House, because she became apprehensive of living alone at Branches Park. Ironically, this was to prove fatal.

Although Dennis James Pratt, an ex-employee, was charged with her murder he was found guilty of Rachel Mary Parsons’ manslaughter, in November of 1956. From the evidence produced, in respect of premeditation, it is all too clear that the conviction indubitably ought to have been for that of murder, but Dennis Pratt was impeccably served by his little known barrister, the young Michael Havers, later the eminent and much respected Lord Havers and father of actor, Nigel. Had a murder conviction been secured, Pratt would have faced being hanged.

Pratt was considered to have been a man who suffered from mental weakness (diminished responsibility) but was this really the case? Might he have been lured by another, who promised financial gain, into awaiting a vulnerable elderly lady’s return to her home, after darkfall? Having already been warned by police that very week not to approach Rachel Parsons, was his desperation, fuelled by his alleged belief that she owed him two weeks holiday pay, really sufficient for him to plan to kill her, then rob her? The killing, and the immediate thereafter, had been meticulously thought out, from beginning to end but from then on Pratt blundered his way into captivity. Monetarily, the exercise was comparatively futile and certainly could never have been the considered outcome.

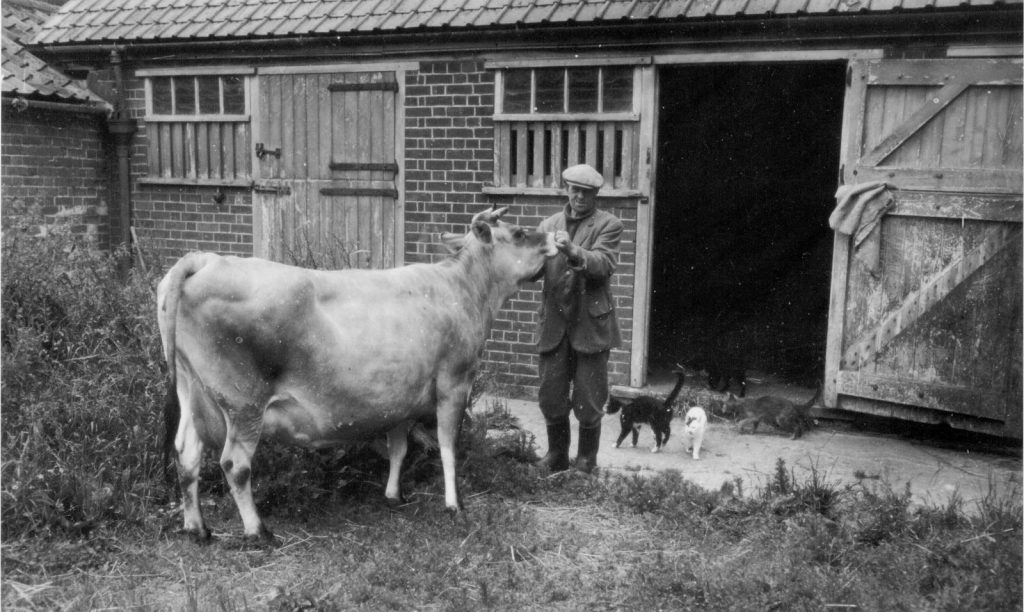

Another hugely curious situation presented itself in the form of Rachel’s intestacy. Could it credibly be believed that a woman of such intelligence and with such means could fail to have ever written a Will, especially as wills had played an important role in her life? Would a woman, who was known to have told others, that, “…I am quite aware that a number of people would like to murder me. They will not kill me easily; I always sleep with a loaded gun by my bed. There are vultures waiting to pick my bones…” not have ensured that these people, so called, would never be in any position to benefit from her demise? Would this devout lover of animals not have made provision for her stable of horses, her twenty-two cats, her Jersey cow, ‘Branches Diana’ and her beloved companion Bruce, the Airedale?

1956 Mr. King with Branches Diana and some of her feline dependants.

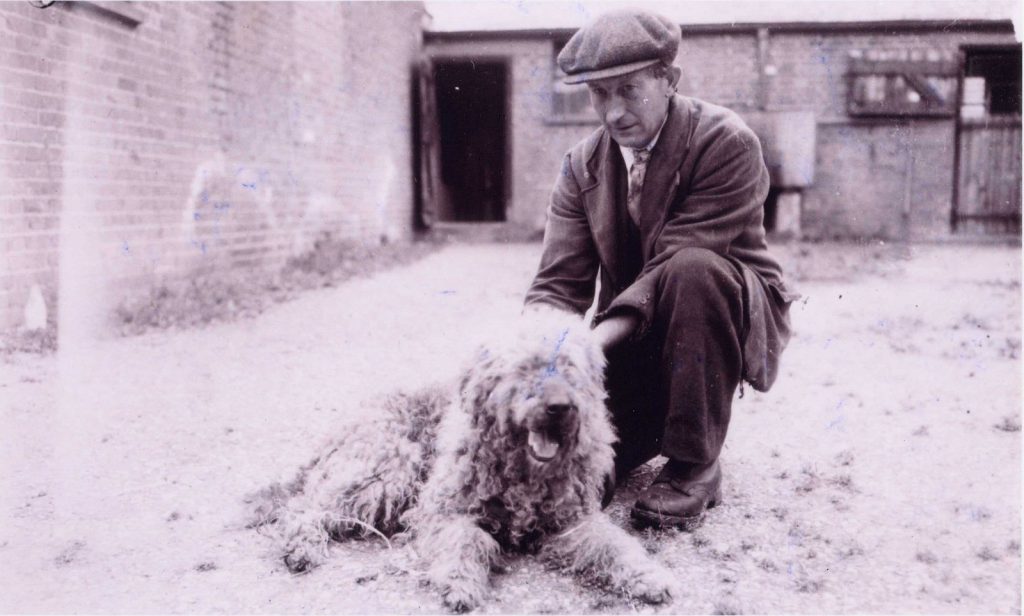

1956 Mr. Claude Level with Bruce.

Rachel Parsons was no stranger to finance, to the law or to common sense, and none can deny this fact. Whilst others considered her method of conducting her life to be a complete pickle, she managed her affairs to her satisfaction. Had this not been the case, she would have afforded what she required. Her weakness were her lack of patience and, later in life, attempting projects which were beyond her ability, given the maturity of her years. Yet she retained an undeterred determination to succeed, and that is a perfect epitaph.

E.L.Raphael invites further anecdotal information or questions of any pertinent sort.